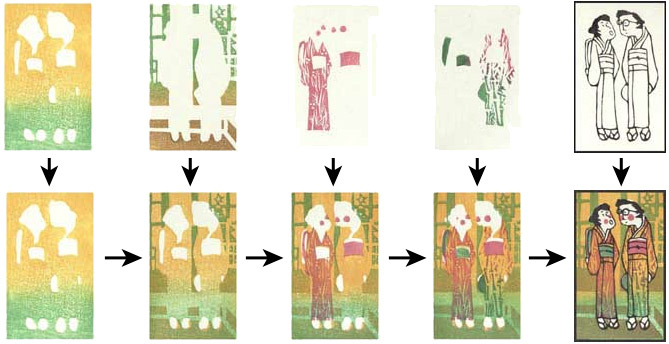

The Process – How a woodblock print is made

Japanese woodblock printmaking, moku (wood) hanga (print), is distinguished from other printmaking techniques by the simplicity of material involved in its creation. Wood, water, paper, pigment, paste, and simple carving and rubbing implements are all that is needed to make a print. The process, however, is labor intensive for the artist, who must undertake the roles of designer, carver, and printer.

Japanese woodblock printmaking, moku (wood) hanga (print), is distinguished from other printmaking techniques by the simplicity of material involved in its creation. Wood, water, paper, pigment, paste, and simple carving and rubbing implements are all that is needed to make a print. The process, however, is labor intensive for the artist, who must undertake the roles of designer, carver, and printer.

To move from the inspiration of the sketch to the mechanics of the print requires thoughtful organization of color and space. Initially, the artist carves a block of wood for each color to be printed. Areas that are not to be printed are cut away, leaving a raised surface, as in the principle of a stamp. Pigment dispersed in a water and rice paste are placed on the block and smoothed across the surface with a brush that looks similar to a shoe brush. A sheet of sized and dampened paper is then placed on the block; proper alignment is insured by two registration marks that are carved into each block at the same place. To print, the artist uses a baren, a flat, hand-held disk that is wrapped in a bamboo sheeth, to press the pigment into the paper.

The Paper: Yamaguchi Hosho

At the edge of an old town in Fukui Prefecture, in an area famous for papermaking, is the home and workshop of Kazuo and Kinuko Yamaguchi. With the guidance of our cousin’s GPS system and the help of neighbors, we found our Otaki destination on damp March day in 2007. In this time of automation, Yamaguchi-san and his wife continue to transform fibers of kozo, or mulberry, into beautiful, strong sheets of washi (Japanese paper) using techniques handed down from seven generations of Yamaguchi papermakers. Finding high quality plant materials for papermaking has become progressively challenging. The harvesting is not an easy task and as the number of suppliers dwindles, papermakers are forced to seek new sources. The process of creating beautiful handmade paper is labor-intensive every step of the way. The information I give on this page is incomplete and offers only a superficial description of that process.

At the edge of an old town in Fukui Prefecture, in an area famous for papermaking, is the home and workshop of Kazuo and Kinuko Yamaguchi. With the guidance of our cousin’s GPS system and the help of neighbors, we found our Otaki destination on damp March day in 2007. In this time of automation, Yamaguchi-san and his wife continue to transform fibers of kozo, or mulberry, into beautiful, strong sheets of washi (Japanese paper) using techniques handed down from seven generations of Yamaguchi papermakers. Finding high quality plant materials for papermaking has become progressively challenging. The harvesting is not an easy task and as the number of suppliers dwindles, papermakers are forced to seek new sources. The process of creating beautiful handmade paper is labor-intensive every step of the way. The information I give on this page is incomplete and offers only a superficial description of that process. Kinuko-san’s work begins with the initial washing of the mulberry bark. Time spent cleaning and filtering impurities from the mulberry is extensive. It is obvious that water is an essential part of papermaking. Kinuko-san lifted the heavy cement lid of a well to show us where their water is stored underneath the workshop. When I asked about the temperature of the water, Yamaguchi–san said that it felt warm in winter and cold in summer.

Kinuko-san’s work begins with the initial washing of the mulberry bark. Time spent cleaning and filtering impurities from the mulberry is extensive. It is obvious that water is an essential part of papermaking. Kinuko-san lifted the heavy cement lid of a well to show us where their water is stored underneath the workshop. When I asked about the temperature of the water, Yamaguchi–san said that it felt warm in winter and cold in summer.

The garage-like building of the main workshop has a sign above the door aptly stating: “Super Quality Paper”. As we entered the front room of the workshop we were handed aprons and boots to don; this room is where all the wet work happens. A second room was raised and much drier. There we saw bundles of mulberry bark. One wall looked like a huge closet and was completely filled with drying boards stored like vertical files. Around the top of the walls in this room were the woodcuts of the many artists, famous and not, who used Yamaguchi hosho and had sent their prints in gratitude.

The garage-like building of the main workshop has a sign above the door aptly stating: “Super Quality Paper”. As we entered the front room of the workshop we were handed aprons and boots to don; this room is where all the wet work happens. A second room was raised and much drier. There we saw bundles of mulberry bark. One wall looked like a huge closet and was completely filled with drying boards stored like vertical files. Around the top of the walls in this room were the woodcuts of the many artists, famous and not, who used Yamaguchi hosho and had sent their prints in gratitude.

Yamaguchi-san begins his magic as he dips a wide frame, lined with a bamboo screen, into a vat of the milky water of softened kozo. Like the rhythm of the tides, he rocks the tray up and down, each wave spreading fibers over the screen. Back and forth, in and out, at seemingly predetermined angles, the frame is rocked. The sound is like water lapping up on the shore. A smooth layer of paper appears like untrodden sand left as the tide recedes. One can only stand in awe, watching the artistry of years of experience. I doubt if the act is as poetic after standing hour after hour, but Yamaguchi-san has the appearance of a man fully enjoying his role.

Yamaguchi-san begins his magic as he dips a wide frame, lined with a bamboo screen, into a vat of the milky water of softened kozo. Like the rhythm of the tides, he rocks the tray up and down, each wave spreading fibers over the screen. Back and forth, in and out, at seemingly predetermined angles, the frame is rocked. The sound is like water lapping up on the shore. A smooth layer of paper appears like untrodden sand left as the tide recedes. One can only stand in awe, watching the artistry of years of experience. I doubt if the act is as poetic after standing hour after hour, but Yamaguchi-san has the appearance of a man fully enjoying his role.

The paper is stacked and then placed on wooden boards to dry. Kinuko does the final checking of each sheet in a bright room of their newer home behind the workshop.

The paper is stacked and then placed on wooden boards to dry. Kinuko does the final checking of each sheet in a bright room of their newer home behind the workshop. The original Yamaguchi homestead is beside the workshop. In that beautiful old structure of wood, tatami, and sliding screens, we were treated to a wonderful feast for both the eyes and the appetites. As we were served a meal so graciously prepared by Kinuko and her daughter-in-law, my eyes turned to the tokonoma. The tokonoma is a small, raised alcove in which something of beauty is displayed, like a scroll, flower arrangement, sculpture, etc. When I looked in the tokonoma, there was the hanga of my sensei, Tomikiichiro Tokuriki. I never knew he had used Yamaguchi hosho. The moment was very special.

The original Yamaguchi homestead is beside the workshop. In that beautiful old structure of wood, tatami, and sliding screens, we were treated to a wonderful feast for both the eyes and the appetites. As we were served a meal so graciously prepared by Kinuko and her daughter-in-law, my eyes turned to the tokonoma. The tokonoma is a small, raised alcove in which something of beauty is displayed, like a scroll, flower arrangement, sculpture, etc. When I looked in the tokonoma, there was the hanga of my sensei, Tomikiichiro Tokuriki. I never knew he had used Yamaguchi hosho. The moment was very special. It is such a privilege to use Yamaguchi-san’s paper. The strength and beauty of the paper reflects the strength and beauty of the characters of Kazuo and Kinuko Yamaguchi. Their paper is my gold. To the Yamaguchi’s, I am eternally grateful.

It is such a privilege to use Yamaguchi-san’s paper. The strength and beauty of the paper reflects the strength and beauty of the characters of Kazuo and Kinuko Yamaguchi. Their paper is my gold. To the Yamaguchi’s, I am eternally grateful.